Twenty years ago, a Norwegian freighter rescued hundreds of Afghan asylum seekers off a sinking Indonesian vessel, triggering a crisis that ushered in Australia’s hardline immigration policies.

Read the full story for Al Jazeera here.

Paralympic Games beckon for Hirth

Sunbury table tennis star Trevor Hirth has qualified for the Paralympic Games, which is set to be held in Tokyo later this year.

Read the full article here.

China to build the world’s biggest dam on sacred Tibetan river

In the foothills of the Himalayas, where the ancient Yarlung civilisation established the first Tibetan Empire, China has plans to build the world’s biggest hydroelectric dam.

In November of last year, China’s state-owned media shared plans for a 60-gigawatt mega-dam on the Yarlung Tsangpo river in the Tibetan Autonomous Region (TAR).

Now with the aim of achieving carbon neutrality by 2060, Beijing has redoubled its efforts on its hydropower projects in Tibet, even though the dams have drawn criticism from Tibetan rights groups and environmentalists.

China’s LGBT community expresses disappointment after Shanghai Pride cancelled indefinitely

Amy Yang always wanted to travel outside of China, but she didn’t expect her life to change as much as it did.

Having now completed her studies, the 27-year-old owns her own accessory business and says her current life, living with her girlfriend in Melbourne’s CBD, is beyond her wildest dreams.

Read the full article here.

Stop watching the grass grow

Oliver Lees examines the case for an alternative lawn.

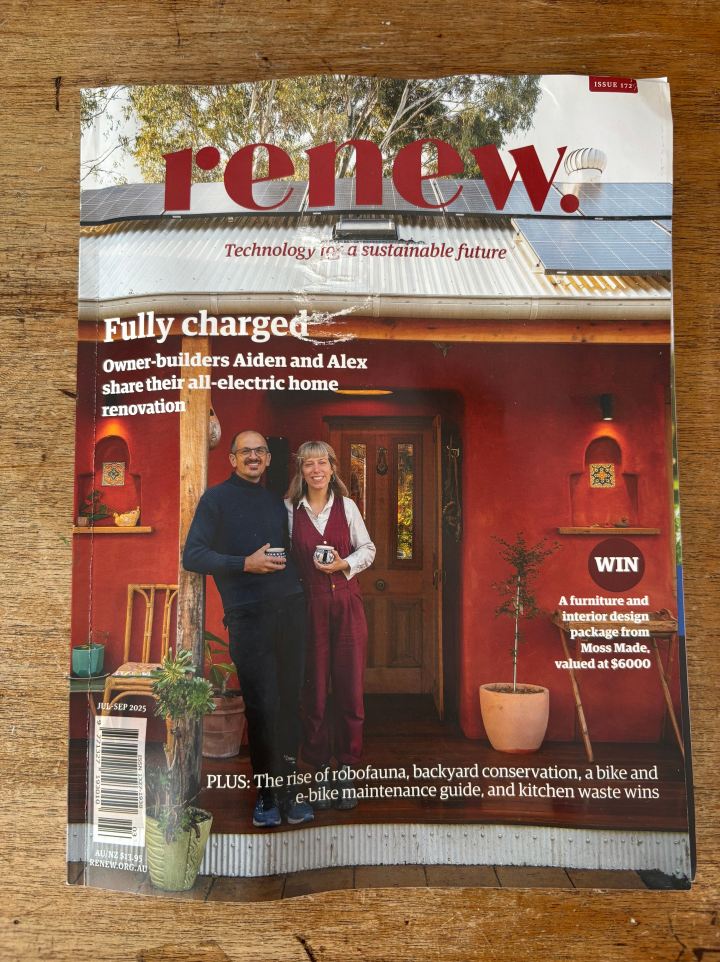

This article appeared in issue 155 of Renew Magazine, published in April 2021. I have republished the article here with permission from the publisher.

Like all facets of Australian life, our urban environments have undergone considerable change in keeping up with the demands of an increasingly sustainable and contemporary society. Once considered an eyesore, solar panels are now widely accepted as an ethical energy alternative, with more than two million residential setups on rooftops across the country. Likewise people have reconsidered how they manage their waste: nearly all Australians recycle, whilst roughly a third of the population have developed at-home composting. The modern home has undergone a revolution of its own, with homeowners opting for energy efficient light bulbs and water saving shower heads.

But there is one feature of the Australian home that has stood the test of time, remaining a ubiquitous sight across the country—the common grass lawn.

Grass is a mainstay of Australian gardens, and is the default option in both front and back yards. It certainly has its virtues: as well as being familiar and relatively manageable, a well-kept grass lawn looks great. As many have gravitated closer toward cities—and therefore forfeited their ability to own a larger chunk of land—these green spaces are perhaps valued more now than ever before.

But what if there was a way to get even more out of your limited garden space? What if, instead of a yard that was purely green in aesthetic, you had an area that could be cultivated into an area of actual abundance?

Is there a problem with grass?

Maria Ignatieva, a professor of landscape architecture at the University of Western Australia, has done extensive research into the historical proliferation of lawns dating back to the Middle Ages, and is currently researching lawns as an ecological and cultural phenomenon in Perth. Professor Ingatieva’s research has found that these spaces became a symbol of upper-class European society, demonstrating an element of prestige and power. The popularity of lawnscapes took off in the early 18th century, as Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown redefined the English landscape, styling gardens with dazzlingly well-kept lawns. In private homes as well as public spaces, a neat stretch of grass allowed humanity to demonstrate its ability to tame nature in a controlled manner.

Australia’s culture of lawn cultivation is an heirloom of our colonial history, just as it is in New Zealand and the United States. But lawns were also highly symbolic in the early days of settler society in Australia, as newly arrived colonists attempted to achieve the classic English garden in the less forgiving climate of the Australian outback. Like other popular elements of imperial style, a grass lawn was considered in opposition to the uncivilised wildness; a means of differentiating oneself from the harsh native scrub which represented indigeneity. It’s not just the aesthetic that’s been imported either, the most commonly used grasses in Australian backyards, buffalo, kikuyu and couch grass, were all introduced from other parts of the world. Whilst each type of grass is unique in their blade structure and suitable environments, they’re the same in that each of them create that classic green carpet look many people crave.

Clearly, introduced plants are a problem in a fragile ecosystem like that of Australia—but the fact that so many lawn grasses are introduced isn’t the only reason to consider alternatives. From an ecological perspective, grass lawns can stunt the biodiversity of the soil. Common grasses are considered a monoculture and in some circumstances can actively detract from the productivity of the garden. With its wiry blades and long underground roots, couch grass is a common suspect that is known to pop up and invade garden beds.

Those with pollen allergies will understand how difficult those hayfever months can be, and landscape gardener Matt Fiddes, owner of Melbourne-based Blume Landscapes, explains that a little-known advantage of getting rid of your lawn is that doing so helps reduce pollen count.

“Because pollen is windborne you can’t really avoid it,” he explains. “But the best thing you can do is try and minimize it around your house, and you can do that by cutting back on your grass space.”

Regular grass also requires regular mowing, which can be time consuming and emit harmful levels of carbon dioxide.

Still, it’s important to remember that grass isn’t inherently bad. Professor Ignatieva emphasises that grass is not somehow inherently evil and in need of immediate eradication. In fact, she says that grass plays an important part in the Australian ecosystem.

“Lawns [have] many positive [effects] One of the most important is their cooling effect and another is for recreation and sport,” she said. “So it is important to find a good compromise that corresponds with local conditions.”

A decade’s experience in landscape gardening has also taught Matt that striking a balance is important.

“Nothing can beat that classic turf look, but lawn alternatives definitely deserve a spot in the landscape,” he says.

Finding an alternative

Having spent five years feeling displeased with her front yard, Sarah Reid finally gathered the courage to make some changes. Living in a heritage listed corner plot in her namesake inner-city Canberra suburb of Reid, Sarah said she wanted a more dynamic garden, one that would not only withstand a dry climate, but would also be useful and filled with interest.

“It was pretty sad and depleted,” she said, in reference to the couch grass which used to occupy her front yard.

“I wanted something friendly and biodiverse, with flowers to encourage the bees and other wildlife.”

Working with her husband, Sarah pulled out her cotoneaster hedge and removed the widespread couch grass (which she described as her “bane”) by smothering it with cardboard and fresh soil.

In its place, she planted a variety of native flowers; a neat row of lavender which lines the pathway; and ground cover to stifle the returning weeds, including myoporum and salt bush. She now finds that edibles often sprout spontaneously around her vegetable garden where previously there were weeds.

The greater diversity of plant life in the garden has welcomed wildlife, where previously there was none: lizards scuttling from beneath stones; baby birds coming in to land; and butterflies and bees making use of the many flowers. The transition is now well established; Sarah estimates that the transformation took about 18 months, but says it never felt like too much work.

“Considering how big the change has been, I don’t feel like it has been an enormous amount of effort,” she said.

“I wouldn’t worry about being held back by a lack of experience, it’s all about enjoying the surprise of what unfolds.

“it was just really fun, and I loved seeing the changes.”

Professor Ignatieva says the careful planning of a dynamic garden space like Sarah’s not only makes sure the space is of use—unlike many purely aesthetic grass lawns—but also makes everything healthier.

“Employing different landscape design patterns—colour and texture—as well as providing more biodiversity, [creates a more] ecologically friendly wildlife habitat and a healthier environment.”

Instead of spending her gardening time pulling out weeds and mowing the lawn, Sarah says she spends most of it inspecting the growth of her many projects. But despite her best efforts, the couch grass still pops up from time to time. Determined not to use poisons, Sarah will either pull the persistent strands out by hand to stop them invading her flower beds, or—if weather permits—use a small propane burner.

Can add biodiversity research here if need be.

Street-facing fences are prohibited in Canberra, which has made the change all the more rewarding for Sarah. Often as she’s working in the front garden, her neighbours will walk past and stop for a chat, commenting on all the progress she’s made, adding another way in which she has become more engaged with her environment.

“To me, the whole experience has really demonstrated just how positive being in your front yard can be,” she said.

Searching for a similar solution to her own problem of encroaching kikuyu grass, Catriona—who lives in the Melbourne suburb of Northcote—first tried myoporum as a replacement. Myoporum is a suitable grass replacement because it maintains a low, dense ground cover that will often deter weed growth and grow no more than 30cm tall.

But after a short growth period, the myoporum died off, likely due to a lack of sunlight in winter. Like any garden project, there is an element of trial and error involved in working out what best agrees with the soil. (Sarah went through a similar period of experimentation, trying out different configurations until hitting upon one that worked.)Despite the setback, Catriona remained determined to find another alternative to suit her native 3×3 metre garden plot. And she did, in the form of dichondra.

Matt from Blume Landscapes says in his experience—despite it still not being very popular amongst his clients—dichondra is one of the best options for people looking for something other than grass. He also cites other low-lying alternatives like moss and mint as practical, no-mow alternatives.

“[Dichondra] is super simple [to plant], and then once the plants are established, they take care of themselves,” he said.

Catriona bought everything she needed for her new lawn from a local nursery. She used a combination of seeds and seedlings and completed the whole job herself. Like myoporum, dichondra creates a low ground cover, growing only as tall as 10-15cm, with small kidney shaped leaves. There are two popular options for Australian gardens: repens and emerald falls. Whilst the former is used for general ground cover, the latter can be used on areas like retaining walls, to create a thick cascade effect. Dichondra is also self-repairing, meaning if it’s trampled or flattened for some reason, it’s perky stems will pop back up in a couple of hours. Or, as Matt puts it: “As long as you’re not playing cricket on it, then it’s fine.”

In some respects, dichondra is hardier than grass. It very rarely dies off in patches—a recurring problem with common grass lawns, often due to being overexposed to the sun, or from being cut too short. Another, stinkier nemesis for grass is pet dogs, whose highly nitrogenated urine can simply burn through turf; again, this problem doesn’t affect dichondra.

All in all, it took around a year for the dichondra to properly cover the space, and Catriona couldn’t be happier: “The weeding now takes only five minutes, whereas it used to be an absolute nightmare,” she says. “I’m definitely a massive advocate. I tell everyone I can.”

A movement

The concept of an alternative lawn is, of course, not an entirely new concept. But the reimagining of conventional garden spaces has collected momentum in recent years.

In 1999, Heather Jo Flores founded Food Not Lawns, an online, international collective of people looking to make the most out of their yard through community engagement. Through forums and online courses, community members organise seed swaps and garden parties. The website now has over 80,000 subscribers from around the world, where Heather says “many thousands of people are involved now in our free online courses and learning to turn their lawns into permaculture gardens.

“In general I think that people embrace any opportunity to reconnect with nature, especially if they don’t even have to leave their houses to do it!”

Over 20 years of travelling the United States, helping people with their garden projects, Heather believes anyone is capable of changing their environment for the better, especially when you can find like minded people to help you along the way.

“If you’re competing with a well established patch of grass the best way to get started is to dig it all out, then add your mulches,” she said, before stressing:

“Connect with the neighbors. No lawn is an island.”

A different relationship with your garden

With the bulk of the work behind her, Sarah is glad she finally made the call to uproot her space and try something new a year ago.

Whilst she made repeated mention to the ways in which the garden seemed to work better together—the composted soil birthing edibles and colourful flowers; an in-ground worm farm feeding the raised garden bed—her biggest takeaway was just how useful the space now felt, and how that had changed the way she thought and felt about her garden.

“In the space of a year, it’s gone from just dirt and straw to something with lots of life in it, it’s like there’s more information in there now, much more activity.” she began.

“It’s given me quite a different relationship with the garden.

“It’s like the garden and I have these conversations, and it tells me what new thing is happening in its life.”

Is hard rubbish really the best we can do?

This article appeared in a previous issue of Renew Magazine. I have republished the article here with permission from the publisher.

It’s a sight of Australian suburbia as familiar as the eucalypt: piles of unwanted household items littering the nature strip. While the frequency and nature of these hard rubbish collections varies from council to council, nowadays it is understood to be more or less an entitlement of homeownership.

Everything from functioning fridges to widescreen televisions, bedside tables and car tyres, Australia’s hard rubbish collection system is burned into our culture as a convenient way of getting rid of awkward items we no longer require that aren’t suited for the kerbside bin – so much so that a subculture of salvaging items for reuse is common practice.

But herein lies a central issue with the way in which we view these collections, because if scavenging unwanted goods from your neighbours supposed ‘waste’ pile is so straightforward, have we lost sight of the reason this system was created? And if so, can we change the way we view hard rubbish?

How does the system work?

Of course, it is essential to have options for waste disposal. According to the federal government’s latest national waste report, local government and household waste weighed in at 14 megatonnes in the 2020-21 financial year, or, if we look at our country’s entire waste production for that period, it works out to be just under three tonnes of waste per person.

Michael Strickland has been in the business of hard rubbish collection for the past 25 years. As a project manager for WM Waste Management Services, he and his team have contracts to collect from 16 council areas, mostly in Melbourne but also in regional areas such as the Latrobe Valley.

In the two and a half decades he’s been in the work, Michael admits the job has remained mostly unchanged, except for the arrival of new regulations in the collection and disposal of items such as e-waste and tyres. The most common items are everyday household things, but that’s not all that makes the pile.

“I’ve heard of all sorts of things like a coffin has been found [in hard rubbish], and we get heaps of mannequins as well,” he said.

The majority of councils in Victoria now work under a system of hard rubbish bookings where homeowners can book one or two collections per year. Area-wide services are also used in a handful of council areas, but these are becoming less common. Michael’s team is then called out to the location with a compactor truck and a tray truck. The tray truck is used in the context to collect salvageable items, but despite what some might think, Michael says this does not apply to any item that could be repurposed.

“Most things get compacted, it’s only if we’re not allowed to compact them that we don’t compact really,” he said. “The tray truck would pick up things like fridges or e-waste – everything else would go into the compactor truck.”

There are exceptions to this, with some councils offering services for separate mattress and tyre collections, but everything else, no matter whether it’s in good condition, is crushed on the spot.

Michael says it’s a frustrating aspect of his work seeing so many perfectly good items destined for landfill. “Once it’s out in hard rubbish like there’s not a lot of stuff we can salvage and reuse,” he says. “If you thought it was valuable, then why are you putting it out on the street? We’re sort of the last resort, really.”

But rather than operating as a last resort, hard rubbish is used as a means of getting rid of anything. The ABC’s War on Waste series found that 85 per cent of furniture left for kerbside collection is not recycled.

Dr Trevor Thornton is a senior lecturer in hazardous materials management at Deakin University. As well as previously working with Victoria’s Environment Protection Authority, he has studied waste management strategies both here and abroad.

In the early 20th century, collection services were limited to specific items such as empty beer bottles and scrap metal. Landfill sites were less regulated and it was common for families to drop off items and even scavenge directly from these piles. Dr Thorton says once kerbside recycling was introduced in the 1980s and regulations around tip sites tightened, the creation of the hard rubbish collection process we see today arrived as a natural progression.

While these changes made it more convenient for people to dispose of things, by removing ourselves from the process, it also fundamentally changed the ways in which we view waste management.

“We’ve made it easy for people just to get rid of things without thinking of the quality of it,” Dr Thorton says. “Landfill space is quite valuable and we’re running out of it. I guess we’ve been fortunate in Australia, we don’t have the population densities of Europe and America.

“That’s the mentality I think in this country that, yeah, I’d love to recycle, but it’s easy for me just to get somebody to come and pick it up and take it away.”

The Taiwan example

Filling the gaps

While hard rubbish collection appears rooted within the function of local councils, there are efforts happening beneath the level of government to improve standards. In Melbourne’s inner northern council area of Darebin, community member Jo Press was compelled to make changes when she saw a compactor truck in action in 2019.

“It was a little disconcerting, because hard rubbish is meant to be rubbish, you know, of no use anymore,” she says. “When I saw these things being crushed I realised that was actually what happens, so I just felt I had to do something, that this was terrible.”

Jo teamed up with fellow Darebin resident Jackie Lewis, and in 2020, created the Facebook page Darebin Hard Rubbish Heroes. The idea was that instead of subjecting reusable things to the kerbside where they could be crushed or damaged by the weather, instead individuals could post items they no longer needed and have them collected directly.

The page took off immediately, with upwards of 1000 followers in the first week and today more than 22,000 total.

“When we started we saw there was a real need for helping people rehome things, because there’s a lot of barriers,” Jo says. “Some people don’t drive, some people have mobility issues and they can’t lift and move stuff. People accumulate a huge amount of stuff in their lives, and I am living proof of it. It’s just kind of part of being human in a wealthy country.”

During Melbourne’s stretch of strict COVID-19 lockdown measures, members of the group would livestream themselves walking down the street and identifying decent items and even helping to deliver them directly to people’s homes.

Now incorporated as a charity with a core of nine committee members, the group has expanded its remit. They’ve run repair workshops, created a recycling hub for harder to recycle items like blister packs and bottleshops, and even run their own trash and treasure pop up shops. The largest of these came last year, when Jo and the team were able to utilise a council grant to rent out a former garage space to house and resell all sorts of found household items. In a three month period, the group collected a total of 13 tonnes of otherwise useful things.

In 2020, not long after Darebin Hard Rubbish Heroes was founded, the team created a survey for its members and received 664 responses. They found that a third of all respondents had only learnt in the past 12 months that most things placed out for hard rubbish would be crushed.

Jo says the survey data points to the most important lesson she’s learnt while attempting to improve sustainability outcomes in her neighbourhood.

“I think the biggest thing is in educating people,” she said.

“There’s always going to be a group of people that will do stuff, and there’s going to be a group of people that will never. But there’s a huge group in the middle.”

Finding a balance

Even as someone deeply committed to living a more sustainable lifestyle, Jo admits that waste management is a naturally complex issue. “I still, almost every day, ask myself: can this go in that bin?” she says. “So think of all those people who don’t know a lot. They’re going to be having even more struggles too.”

Although she’s spent the past few years addressing the misuse of hard rubbish, Jo still sees it as an important cog in Australia’s waste management system.

So rather than doing away with it completely, she argues that councils and community groups like Darebin Hard Rubbish Heroes can be the cog that informs people to make better decisions.

And there are other community services and policy suggestions that are working toward the same aim. In 2021, the federal government’s productivity commission released a report with recommendations to strengthen the right to repair. In essence, the report found there are too many barriers created by companies to extend the usability of products, which in turn is exacerbating costs and issues of waste and e-waste management.

Thornton says this also created a push for product stewardship schemes, where large companies that sell items like televisions and furniture are required to also provide a recycling service for those items. “I think that’s something that we need a lot more of, you know, if you sell it, then you’ve got some responsibility to ensure that there is a system in place,” he says.

Since 2015 repair cafes have started to pop up across the country, with 13 in Melbourne alone. These local organisations provide a free repair service for all sorts of household goods, such as electronics, bikes, clothing and furniture.

On a personal level, Jo’s home is testament to her reuse mindset. In her courtyard there is a small circular outdoor table, salvaged from a neighbour’s nature strip and resprayed with an orange finish. In her living room she is working on a new coffee table, which will feature an analog clock face serving as the table face fixed to a set of old chair legs. Most of all she’s appreciative of the ways in which the local repurposing collective has connected herself and others to their own community in a practical and meaningful way.

“There’s a lot of stories o”f people who’ve been in situations where they’ve found the support of the group,” she says. And yeah, a lot of people who have connected through the group, which is kind of amazing. I can’t say it’s restored my faith in human nature because I always have felt people were good, but it doesn’t hurt at all.”

Becoming a conservationist in your own backyard

This article appeared in issue 172 of Renew Magazine, published in July 2025. I have republished the article here with permission from the publisher.

It’s no secret that right now Australia’s environment is under immense strain. Biodiversity Council Australia is clear in its assessment: we are facing a biodiversity crisis.

Australia is one of only 17 nations globally considered to be megadiverse, meaning much of this life is unique to Australia. In the fight to preserve some of the most at-risk life on Earth, we carry a disproportionate responsibility, and right now we are failing. Decades of industrialised resource extraction, the deleterious effects of climate change, and a lack of forward-thinking government policy has enabled the problem to fester.

But rather than submit to this bleak state of affairs, people are taking matters into their own hands. Through innovative local projects, native planting and expansive rewilding projects, a grassroots biodiversity movement has been growing steadily, one that might hold the key to fundamentally reshaping the way we consider our relationship to nature.

Our conservation context

A further look at the research underpinning Australia’s biodiversity context makes for grim reading.

Last year alone, 41 species of flora and fauna were added to the threatened list, which in total features more than 2000 names.

But there is another set of statistics worth mentioning here. Each year, Biodiversity Council Australia surveys the public’s feelings toward conservation. A staggering 96 percent of people agree that more needs to be done to protect the environment, with waste and pollution, extinction of native animals and the loss of natural places at the top of the list of concerns.

Biodiversity Council member and professor Sarah Bekkesy from RMIT University is hopeful a shift might be underway. She is among a large cohort of environment advocates that is asking the federal government to contribute one percent of its budget toward nature. She says the data provides a clear mandate for greater environmental protection.

“It shouldn’t be an ideological topic. So much of our economy is dependent on nature and having healthy environments,” she says. “It’s actually making sure that we are healthy, because our own health is so intrinsically linked to having doses of nature and experiencing nature and having a clean environment.”

On an individual level, Professor Bekkesy says it pays for people to consider their spending and consumption habits. Simple changes like avoiding eating non-sustainably harvested fish, eating less red meat and even purchasing sustainable pet food options can have a big impact.

So too are the big choices, like where you choose to live and how that home is made.

“Your choice of housing is one of the most significant things that you can do for biodiversity,” she says. “About a quarter of the economic activity impacts on biodiversity negatively is in the construction industry.”

Hollow… is it tree you’re looking for?

On a dry paddock in the north-eastern suburbs of Melbourne, an arborist is halfway up a towering gum tree using a specialised power tool called a Hollowhog. His mission is not one of destruction. In fact, his work will bring more life to the environment. He uses the Hollowhog to drill where a hollow has started to develop, doing so carefully so as not to damage the tree’s living tissue while creating a habitat that can be used by wildlife.

This effort has been spearheaded by retiree Judith Venables, who has poured much of her free time into finding ways to help local wildlife and the environment. I should know, because I am her son. Our family home is on a five-acre property in Lower Plenty. Due to planning restrictions from the last century, many of the homes in the neighbourhood, ours included, are unable to subdivide, leaving them with mostly empty paddocks that are seldom used.

Hoping to rectify that in some way, Judith set about planning her local tree hollow project.

“I realised walking around the neighbourhood that there were lots of old gums where this technology could be useful,” she says.

“Given the loss of habitat and the loss of large trees that are suitable for hollow dwellings, I thought that I might be able to get an environmental grant so that this work could be carried out around the neighbourhood.”

Her local council backed the idea, with a $10,000 grant to employ three arborists to work over three days. She did the legwork herself: knocking on neighbour’s doors to ask if she could take a look at their trees.

In total, the arborists worked on six large gum trees, resulting in the formation of 43 new hollows.

A few holes in a tree might seem insubstantial, but the loss of these habitats across the landscape is one of the major challenges threatening species. Nest boxes can also be useful, but not all creatures are willing to use them. Some 300 species of Australian animals depend on these environments, and often move between them with regularity.

In The Forest Wars: The Ugly Truth About What’s Happening In Our Tall Forests, internationally renowned forest expert professor David Lindenmayer describes his seminal research tracking the Mountain Pygmy Possum from 1990 to 1992.

“The results are extraordinary… I discovered that each possum moves regularly from one tree to another. Over a year and a half of tracking, I found that an individual possum might use more than a dozen different trees. Our research has shown clearly that the way animals use large old trees is far more complicated than anyone ever thought.”

The extremely slow pace of hollow development and the significant clearing of old growth trees are the major factors making life harder for animals like the Mountain Pygmy Possum, which is critically endangered.

Mum’s grant also helped fund the purchase of two motion-activated cameras that capture any new life checking out these new spots. Already, the signs are promising.

“So far there’s been a lot of interest from rainbow lorikeets, also quite a bit of eastern rosella interest,” she says. “There’s been brushtail possums and ringtail possums. It’s lovely, I get the photos sent through to my email and it’s always good to see who’s checking it out.”

Gardening for wildlife

As Biodiversity Council Australia’s report indicates, people want to see native environments restored. According to their survey, 86 percent of respondents were concerned about the loss of native plants and animals.

One group that was created to help turn this sentiment into action is Gardens for Wildlife. Since 2006, the organisation has been visiting homes and advising homeowners on what they can do to make their backyard more welcoming to wildlife.

The concept was developed by Jan Jordan, who had developed her own butterfly garden and was determined to protect it. When her attempt to seek assistance from the state government for her project failed, she recognised there was a gap in the market for people like her who wanted to do more but didn’t know where to start.

I met Irene Kelly, one of Jan’s earliest collaborators, at her home in an outer eastern suburb of Melbourne. She greeted me with a jar of homemade loganberry jam. As the current president of Gardens for Wildlife, she remembers Jan coming to her with the idea.

“I thought oh my god, this is absolutely what we need,” she says. “We need people not only to be doing it on their own property but to trigger something in them that makes them aware that it’s valuable. Knowledge is everything, people will do something if they know how to.”

Over two decades, the idea has flourished. Gardens for Wildlife now has backing from 22 council areas in Victoria, with a further 27 councils considering the program. The process is simple; residents within a participating council can register their interest. Two volunteers then attend the property to check out and listen to what they’d like to achieve and advise them on the best mix of flora to make it happen.

Irene says while they are there to provide instruction, consultation is a crucial part of the process.

“It’s very important that I know what they’re interested in because what’s the point of me going in and telling them they should have this, that and the other in their garden, when they may not want those things,” she says.

“It’s that personal connection that our own research has shown us makes a huge difference.”

More than 1,600 participants have now had the Gardens for Wildlife treatment, and the organisation has no plans of slowing down. Earlier this year Kelly flew to New South Wales to train a new team of guides. With one program now operational there, the organisation has recently adopted Gardens for Wildlife Australia, with a plan to roll the initiative out across the country.

Professor Bekkesy says this work in urban areas is just as crucial as efforts to save remote landscapes.

“The most critically endangered ecosystems in Australia are on the edges of Melbourne, Brisbane, Sydney, Perth. It’s not actually a trivial thing to be part of trying to save species in the suburbs.”

After our conversation, Irene took me on a tour of her own front garden. When she and her husband purchased the property in the 1970s, they started their own journey of understanding what a native garden might look like.

I counted at least six bowls suitable for bird bathing dotted around the space. She pointed out the lomandras and the correas planted to attract butterflies, and the prickly thickets suitable for small birds.

The understory was complimented by a large gum, and we paused for a moment to locate the musk lorikeet happily chirping above our heads.

“When I walk around the garden, I really associate myself with that joy that you get out of seeing a new plant grow or flower,” she says.

Forging new forests

When it comes to biodiversity, forests are the richest environments we have. But since colonisation, Australia’s forests have been decimated by forestry practices. Professor David Lindenmayer uses this example to illustrate the point in his aforementioned book on Australian forestry.

“At the time of British invasion it would have been possible to walk the roughly 1,500 kilometres from Melbourne to Brisbane through almost continuous temperate woodland,” he wrote.

“Now, 95-99 per cent of that woodland is gone… cleared for cropping and livestock grazing, with the vast majority of remaining patches smaller than one hectare.”

In one study, professor Lindenmayer found that places proposed for logging in Victoria in 2019 were important habitats for approximately 50 of the state’s most threatened species.

Despite the fact that native logging continues in many parts of the country, there has also been a collective awakening to the crucial role these environments play.

There is a growing expectation that businesses and individuals should be mindful of their carbon emissions, thus driving them to invest in reforestation efforts. Greenfleet is one organisation that plants native, biodiverse forests to help its clients offset their carbon impact.

Working on a minimum of five hectares, Greenfleet engages a landholder to revegetate a space, which is often unused former farming land. They then enter into a 100 year agreement, which allows them access to maintain and protect the forest as it develops.

Greenfleet’s revegetation general manager Alex Paddock says the organisation’s work is attempting to undo some of the harm done to the environment.

“Various approaches and government policies in a lot of cases in the past have led to what I think is dramatic over-clearing and a total lack of balance in the landscape,” he said.

“There are many areas in Australia where you can look from one horizon to another and not see any native ecosystems.”

Forest ecosystems are complex and can take many years to develop. In 2023, Greenfleet revisited a forest in Noosa they’d planted 20 years earlier to see what kinds of changes had been made. They spent the day walking through the space, documenting what they say. A total of 43 new species had made a home in the fledgling forest. Acacias, banana bushes, broadleaf brambles and palm lilies, just to name a few. Greenfleet conducts its planting in rows, but over the two decades those rigid lines have dissolved, making way for a more natural sprawl.

Mr Paddock says the findings are significant. “We get birds and other creatures that are bringing with them seed and new species from other forests surrounding that site and those species are now growing in our forests,” he says.

“It’s an example of how biodiversity and forest ecosystem processes can develop much more complexity if given the opportunity.”

Tomorrow’s habitat

Back at Mum’s place, we’re on our hands and knees placing natives in the soil.

As well as the tree hollow project, she is also three years into constructing a wildlife corridor that she hopes will bring new life to one of the paddocks on the property. This has meant planting hundreds of native trees, bushes and shrubs, and carving out swales to help the flow of rainwater to a wetland at the bottom of the property.

The progress has been slow; many hours of digging into the clay-hardened earth and constructing tree guards to ward off the pesky rabbits. The wetland is now our most regular topic of conversation. The family group chat is populated by previously unlikely animal sightings, such as mobs of kangaroos, frogs and even an echidna.

As we’re finishing up the afternoon’s planting, she points to a diminutive gum planted earlier that week.

One day with a bit of luck, she tells me, it will grow to be as big as the fellow gums in the paddock, which have been there for centuries.

Not in my lifetime, she clarifies. But I can tell that doesn’t bother her.

Renewable tourism hotspot

This article appeared in issue 171 of Renew Magazine, published in March in 2025. I have republished the article here with permission from the publisher.

Located 140 kilometres south of Melbourne, Phillip Island is known to many people as a holiday destination. There you can see the adorable fairy penguins waddle across the sand, attend the annual MotoGP or simply enjoy the selection of excellent surf beaches on offer.

But there is something else happening on the island: a concerted effort to create unique, sustainable systems of managing its energy and environment.

This includes: a large community energy storage system, an additional seven batteries to capture excess solar power generation, carbon neutral farming, and Phillip Island Nature Parks, a world-leading conservation organisation that has made great strides in blending the often conflicting agendas of tourism and environmental protection.

These initiatives are stepping stones toward an objective to be totally renewable by 2030, which is being driven from the ground up by local residents. With a goal that is 15 and 20 years more ambitious than the Victorian and federal governments respectively, it’s clear Phillip Island is attempting to blaze a trail for others to follow.

So, how has this bedrock of sustainability been formed? And does it pose lessons for how we can manage sustainable priorities on the mainland?

Recharging the island

In 2018, around 50 people attended a public meeting to discuss the island’s energy future. Across the San Remo Bridge, which connects Phillip Island to the mainland, members of the Energy Innovation Co-Op in South Gippsland were eager to develop a hyperlocal organisation on the island. Totally Renewable Phillip Island (TRPI) was born, and as the name suggests, has been driving the 2030 net-zero target.

Among the organisation’s achievements so far is the establishment of the island’s first battery energy storage system. The battery is owned and operated by energy service provider Mondo, having won a tender process carried out by power company AusNet. At peak periods such as the summer holidays the number of people on Phillip Island can quadruple. The purpose of this battery is to curb the enormous strain on the energy grid, to prevent black outs and minimise the reliance on diesel generators by powering up to 8,000 homes.

As explained by outgoing TRPI chair Mary Whelan, this major project was a crucial first step in the group’s vision.

“The neighborhood battery storage has been the vehicle for us to have ongoing communication with the community about this whole transition,” she said.

A retired physiotherapist, Ms Whelan has been leading TRPI’s group of dedicated volunteers. Like all organisations of this scale, TRPI has faced issues in retaining reliable helpers. Ms Whelan said the group made the decision to pivot to make the most of its output.

“About three years ago, as a group, we decided we’d retire some of the working groups,” she said.

“We wanted to concentrate on renewable energy, because renewable energy was where the groundswell of interest was.”

The decision to focus on renewables paid off. In the second stream of the Victorian Government’s 100 Neighbourhood Battery project, Phillip Island was recently announced as the largest beneficiary, with seven of the 13 batteries promised to the island.

These batteries, unlike the existing community energy storage system, are not intended to provide a backup in times of electricity outage. Instead, these batteries – which will be installed on the island by August – will support more solar rooftop uptake and capture additional solar power generation. The batteries will charge during the day, mostly from solar, then discharge in the evenings when demand is at its highest. Additional power will be sold on the market by commercial energy business Mondo, with seven per cent of those profits returned to TRPI.

Speaking at an online information session for the project in February, Matthew Charles Jones from Mondo said the local impact of these batteries could have wide ranging implications.

“It will also provide a very real world example of how we make sure that batteries, which are a very proven technology and getting better all the time, how they can be applied at this local stage,” he said.

“We’re in a position to start to respond to the transition and phasing out of coal fired power stations.”

With the community storage system project priced at $10 million and the Neighbourhood Battery allocation of $2.1 million, TRPI has been able to utilise its local influence to maximum effect.

Ms Whelan said establishing and maintaining a broad network was the key to the organisation’s success, which extends from local business, to water supplier Westernport Water, tourism providers and local council.

“My observation is that anyone who’s looking at applications and wondering who they are going to fund, if you have widespread strong support, they will,” she said.

“We’ve acted as a catalyst, really, for all these different organisations… who then want to tell you their story. They want to tell you ‘this is what we’re doing.’”

Farming for the environment

A short drive from Phillip Island’s major town of Cowes, Bob and Anne Davie have been tending to the land for seventy years. When they moved to their then 80 acre plot in 1956 with a loose plan to try their hand at farming, renewable energy was a distant thought.

“When we first came here, there was no power,” Bob said.

“There was no sealed road out the front. It was a dirt road, and we hoped that one day the power would come to this part of the island.

“It was quieter, and a lot easier to get a park in Cowes. You knew everybody in the main street, so it’s changed a lot.”

And just as the island has changed dramatically, so too has the Davie farm in size and ambition. Starting as a dairy farm, Bimbadeen Farm now covers 360 acres and has transitioned to beef farming, as well becoming an early adopter of carbon farming.

In 2009, the local Landcare branch invited farmers to test the carbon in their soil. Bob jumped at the opportunity.

“I was always interested in carbon,” he said.

“It was determined at that time that the carbon in our soils was greater than our CO2 emissions.

“I knew how important it was, and from then on, that was just a matter of trying to increase the carbon in the soil.”

Since learning that his farm was carbon neutral, Bob has been fixated on finding the best methods to maximise his farm’s carbon potential. In addition to growing deep-rooted crops, he recently deployed 3,500 dung beetles. These hardworking insects locate cow manure and roll it into large balls, which they then push into tunnels dug deep in the earth. The process allows the nutrient and carbon rich feces to be deposited into the soil, while also improves the grazing environment for the cattle.

With its clay soil, Bimbadeen has a natural advantage, as the clay particles stop organic matter from degrading, unlike sand soils which are less suited to trapping carbon. Still, the farm faces ongoing issues of soil salinity, a natural enemy of carbon farming. To counter this, Bob uses a spray which combines seaweed and SA1000 – a salt remediation product.

Once the testing process is completed, Bob is able to trade the surplus balance through the Australian Carbon Credit Scheme Unit (ACCU). According to the Clean Energy Regulator’s latest reporting from November last year, the spot price for carbon credits was $42.50 per tonne, up from $34 in September. These prices are in a constant state of flux, as is the carbon yield from Bimbadeen. The carbon trading scheme is not without its critics, with some dissenting voices suggesting that corporations can use the scheme to detract from other, more advantageous emissions reductions schemes.

But in Bob’s case, it’s brought a deeper understanding of his agricultural output and its effect on the climate more broadly. It’s a process that requires constant monitoring and adjustment to get the best outcome. Recently this has proven fruitful, with a 28 tonne per hectare increase recorded at last testing in two paddocks. Bob said he was “stunned” more farmers don’t take the time to test their soil.

“It’s the only crop that a farmer can ever have that never leaves his property and creates an income,” he said.

“With other farming, you have to put a lot of money into genetics, breeding and everything else to get a return from it. With carbon, you build it up, you trade it, but it stays where it is.”

“There would be a lot of farms that would be carbon neutral but they wouldn’t even know it.”

Reflecting on the changes seen in his lifetime, Bob overall is pleased to see the progress being made by organisations such as TRPI. In his own way, he has been advocating in vain to see if carbon testing of the island’s carbon could be carried out on a larger scale.

“In my opinion, the island could be carbon neutral from carbon in the soil,” he said.

“If we can be, why can’t somebody else be?”

An island in the sun

In the summer months, Phillip Island becomes a hive of activity. Many locals damn the congestion brought on by holiday homeowners and tourists, who have piled in cars and tour buses to enjoy the island’s unique offerings. Chief among those is the penguin parade.

The sight of little penguins waddling up the beachfront has delighted visitors for nearly a century. The earliest tours were conducted by a handful of locals in the 1920s. Armed with torches, they would lead small groups of tourists to the beach and wait for their approach.

Now operated by Phillip Island Nature Parks, a great amount of work has gone into ensuring the tourism experience does not come at the expense of the little penguin colony, which is the largest in the world. Mast lighting is used for visitors sitting on a tiered grandstand to see the penguins’ approach, but it is limited to 50 minutes, and has been designed to be wildlife sensitive.

A Phillip Island Nature Parks spokesperson said penguin protection was the core of the organisation’s focus. Recently, capacity at the parade was reduced significantly from 4,000 nightly visitors to 2,600.

“Nature Parks has developed significant expertise in little penguin conservation,” they said.

“With the support of the State Government, it has succeeded in protecting and growing the Phillip Island little penguin colony, which is now estimated at 37,000 across the Summerland Peninsula.”

Any island ecosystem has specific needs, and Nature Parks have a hand in many programs. The organisation is also responsible for extensive revegetation and conservation, which have made strides to improving habitat for the critically endangered fairy tern and bush-stone curlew. In 2017, Nature Parks, in collaboration with local landholders, effectively eradicated the island’s fox population. In 2022, Nature Parks was inducted into the Ecotourism Australia Hall of Fame.

Nature Parks is another organisation that has been working closely with TRPI. Currently 94 per cent of its energy comes from renewable sources at its major tourism locations.

Bass Coast Shire Council mayor Rochelle Holstead said this approach to tourism has a trickle down effect.

“I think it’s a change of psyche,” she said.

“There’s a lot of people now who are looking for that ecotourism experience, and people who are looking for that sort of experience understand the sensitivities around the environments of which they’re visiting.”

Before moving to the Bass Coast, Cr Holstead served as a mayor of Frankston City Council, which is located in the southern suburbs of Melbourne.

Moving from a metropolitan to regional area, and seeing the approach to planning and policy in both e, she knows firsthand how environmental priorities can change depending on your location.

“I think Bass Coast is very environmentally conscious,” she said.

“We’re very focused on sustainability and renewables, and for good reason, because we live in an environment where we see the benefit of it.”

The road to 2030

As TRPI and its partners prepare for the final phase of its vision of carbon neutrality, it will do so under new leadership. Simon Helps has agreed to step into the role of chair in place of Mary Whelan.

Unlike Whelan, Helps has worked professionally in the renewable sector for the past three decades. His range of experience in projects in the spaces of green hydrogen, solar and beyond will assist TRPI to turn the idea of becoming totally renewable – which in many people’s minds is an abstract concept – into a concrete roadmap.

While the science behind this work can be difficult to communicate to the less initiated, Helps believes it’s crucial that people see the working.

“The 2030 target for a lot of people on the island feels like this crazy, hippy, ‘what are you talking about’ kind of thing,” he said.

“Ultimately, it is very achievable and it’s not as far away as people think. We’re about 48 per cent of the way through that journey already.”

While detractors have pointed to the successful tender of the battery projects as minor milestones, he believes they are just one element in a story that has been quietly playing out for some time.

The uptake in the use of new technologies such as energy efficient appliances, LED lights and heat pump hot water systems through government incentives is one of these factors making a significant contribution to reducing emissions.

“Everybody on the island is effectively using 30 per cent less energy than they were in 2011,” he said.

Moving forward, Helps concedes that no matter how organised TRPI is in its coordination, collaboration and communication, there are theoretical elements that can be difficult to predict. The island’s success in achieving net-zero will be dependent on ongoing energy efficiency schemes being carried out by government and larger partners like Nature Parks and Westernport Water.

So far acting as a conduit between these actors and the community, TRPI has made progress that outstrips its diminutive size. Helps said he’s not only confident of reaching this goal, but also setting an example for communities elsewhere to follow suit.

“It’s a really good microcosm,” he said.

“There’s some really good opportunity for some good news out of setting an objective and working hard and achieving it here.

“The thing that makes the island really unique is the people who can be really problematic in other locations, network owners and state government, are all on board here.”

Are companies doing enough to prevent scams?

When Stacey Wagner used Ticketek’s resale website to buy Billie Eilish tickets, she felt confident there would be no issue. As it turned out, she was a victim of an elaborate scam that affected several people.

Push to bring inclusive football to eastern Victoria for people with disability

David used to complete a six-hour round trip on the train every week to play at the closest inclusive team to him in Melbourne’s outer east.

Now, he wants those same opportunities for his community closer to home.

Read the full story for the ABC.

Tim McMahon frustrated as mother’s burial delayed at Bairnsdale Cemetery

Tim McMahon wanted to fulfil his late mother Flo’s wishes by burying her at a family plot in a cemetery in eastern Victoria.

But Mr McMahon’s mother, who died in November last year, still hasn’t been laid to rest.

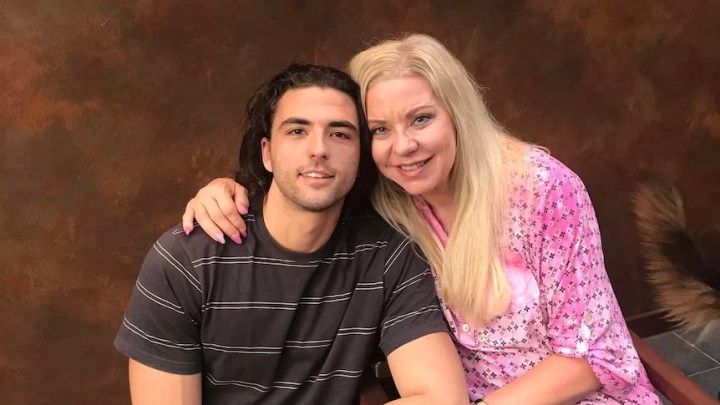

Melbourne mum uses nightmare of son’s prison sentence to help others

It came as no surprise to Jane Jones when her son Zac was sent to prison.

But once Zac was sentenced her struggle entered a new phase as she was forced to contend with the complexities of the corrections system.

A Russian Question And Its Consequences

From the 15th to the 17th of March Russian voters will head to a ballot box and make their choice on who they’d like to see lead the world’s largest country over the next six years.

However unlike other democracies, the validity of this so-called ‘choice’, has over the course of two decades been slowly ground down into a foregone conclusion, designed to cloak the authoritarian intentions of Vladimir Putin.

In this episode, you’ll hear from someone whose home and family has been torn apart by this agenda and a young voter who is holding on to hope despite it all.

Indonesia’s Dancing Democracy

Indonesians will head to the polls on February 14th in a race that has been shaped by modern messaging and an attempt to shake an uncomfortable past.

In this episode, you’ll hear from a former punk rocker turned academic and an early career journalist about what matters to them.